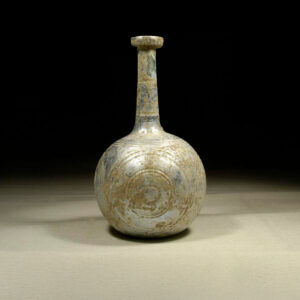

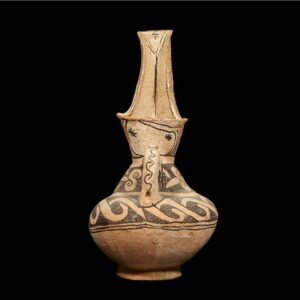

Indian Copper Anthropomorph (Idol)

Type I – i.e. without hieroglyph inscription

This Indus Valley civilization copper anthropomorph is a rare and fine example of abstract silhouettes of human figures that were produced by the indigenous inhabitants of the Ganges river valley. Found together with other implements such as harpoons and rings, the figures were cast in molds from copper and then hammered, with the chisel marks left easily discernible. The natural attractive patina and the earthy deposits are signs of prolonged burial. It has been suggested that these idols functioned as protective guardian spirits.

Four Types of Anthropomorphs

ANTHROPOMORPH FEATURED HERE IS OF TYPE I, i.e. without hieroglyph inscription:

Given that pure copper is a relatively soft metal and most of the objects show little or no signs of wear, it seems likely that their function was largely dedicatory. Hoards of such objects have been found across north India, the greatest concentration being in Uttar Pradesh. The findspots suggest they were ritually deposited in rivers or marshes, though several related antennae swords were recorded in late Indus Valley civilization (ca. 1500 B.C.) burials at Sanauli.

– Type I – semi-circular headed, curved arms signifying ram’s horns, standing with spread legs.

– Type II – (Indus Script ‘fish’ hieroglyph) similar to Type I but with Indus script incription of ‘fish’ hieroglyph.

– Type III – (Seated, with right arm upraised) similar to Type I but with variants of ‘seated posture’ and one right arm lift upwards.

– Type IV – (Indus Script ‘boar’ ligature & ‘yong [sic] bull’ hieroglyh [sic] inscribed) similar to Type I but with Indus Script inscriptions/ligatures of boar’s head and hieroglyph of one-horned young bull.

Paul Yule had identified Type I and Type II artefacts from among the Copper Hoard Culture finds as anthropomorph types based on orthographic features. With the discovery of new artefacts of the Copper Hoard Culture, the typology can now be extended to four types of anthropomorphs. The types are:

– Type I – semi-circular headed, curved arms signifying ram’s horns, standing with spread legs.

– Type II – similar to Type I but with Indus script incription of ‘fish’ hieroglyph.

– Type III – similar to Type I but with variants of ‘seated posture’ and one right arm lift upwards.

– Type IV – similar to Type I but with Indus Script inscriptions/ligatures of boar’s head and hieroglyph of one-horned young bull.

The findspot of Type II “Sheorajpur Anthropomorph” (with ‘fish’ hieroglyph) is Sheorajpur where an ancient Shiva temple has been discovered. The temple ceiling is decorated with metalwork plates of sculptural friezes attesting to the metalwork tradition of the site during the Bronze Age.

Apart from the insribed or ligatured anthropomorphs with Indus Script hieroglyphs, the link to Indus Script tradition is validated by the finds of anthropomorphs in Sultanate of Oman dated to ca. 1900 BCE and to the find of an anthropomorph in Lothal (2500 BCE?). Thus the Copper Hoard Culture can be seen as a continuum of the Bronze Age Revolution evidenced by the Indus Script Corpora of over 7000 inscriptions – all related to metalwork catalogues or data archives.

It is submitted that the anthropomorphs of Copper Hoard Culture are a reinforcement of the Indus Script decipherent as metalwork cataloguing in Prakrtam (Indian sprachbund), a cipher system mentioned by Vatsyayana as mlecchita vikalpa ‘lit.cipher of mleccha/meluhha, ‘copper workers’.

While many anthropomorph examples are of small size which led Paul Yule to infer that they did not have utilitarian value as ‘metal’, some examples have been reported from Metmuseum of anthropomorphs of sizes 4 1/2 x 3 15/16 in. and 6 1/8 x 4 7/8 in. which have led to their identification as axe-heads or ax celts or copper ingots.

Srini Kalyanaraman suggests that all the anthropomorphs are orthographic form hieroglyphs of Indus Script to signify metalwork dharma saṁjñā ‘signifiers of responsibilities (in guild — as artisans/seafaring merchants) or professional calling cards’. Such dharma saṁjñā may have been disseminated as badges to herald or proclaim the holders’ professional competence in metalwork.

RV 1.10.1 indicates ‘worshippers held aloft as it were (on) a pole’ during Indra dhvaja festivals. It is possible that such anthropomorphs were held aloft on poles as exhibits during festivals to proclaim to the people the new competence in metalwork.

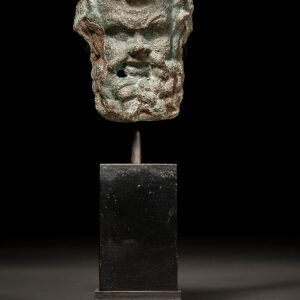

Parallel Anthropomorph in Museum

(located at Allahabad Museum, Allahabad, India):

– Anthropomorphic Figure, Copper hoard culture, Farukkhabad, Uttar Pradesh

– http://museumsofindia.gov.in/repository/record/alh_ald-AM-ARCH-218-7671

Parallel “Sheorajpur Anthropomorph” in Museum

(located at State Museum, Lucknow, India):

TYPE II ANTHROPOMORPH

– Sheorajpur anthropomorph with ‘fish’ hieroglyph and ‘markhor’ horns hieroglyph. ayo’fish’ Rebus: ayo ‘iron, metal’ (Gujarati) khambhaṛā ‘fish fin’ rebus: kammaTa ‘mint, coiner, coinage’. Fish sign incised on copper anthropomorph, Sheorajpur, upper Ganges valley, ca. 2nd millennium BCE, 4 kg; 47.7 X 39 X 2.1 cm. State Museum, Lucknow (O.37) Typical find of Gangetic Copper Hoards.

– http://katalog.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/cgi-bin/titel.cgi?katkey=900213101

– http://heidicon.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/heidicon/239/213101.html

– http://heidicon.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/id/213101

– http://asi.nic.in/asi_museums_lucknow.asp

– http://uptourism.gov.in/pages/top/explore/lucknow/state-museum

Parallel “Saipa Anthropomorph” in Museum

(located at Musée Barbier-Mueller, Switzerland):

– Anthropomorphic figure, Copper hoard culture, Northern India, Doab region, Ganges Valley

– http://www.barbier-mueller.ch/collections/antiquite/age-du-bronze/?lang=en

– http://www.barbier-mueller.ch/collections/antiquite/age-du-bronze/?lang=fr

Parallel Anthropomorphs in Museum

(located at MET MUSEUM, New York City, New York, USA):

– Samuel Eilenberg Collection, Bequest of Samuel Eilenberg, 1998

– http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/39432

– http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/50592

– http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/50588

– http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/50641

Parallel Anthropomorph in Museum

(located at CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART, Cleveland, Ohio, USA):

– Anthropomorphic Figure. India. Bronze Age. Mid/Second Half of the 2nd Millenium BCE.

– Norman O. Stone and Ella A. Stone Memorial Fund

– http://www.clevelandart.org/art/2004.31

Parallel Anthropomorph in Cleveland Museum of Art Mentioned in Scholarly Journal:

“Art of Asia Acquired by North American Museums”, 2003-2004 (p. 113, Fig. 8)

Archives of Asian Art

Vol. 56 (2006), pp. 109-132

Published by: Duke University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20111341

Page Count: 24

cf. Scholarly Publication

Anthropomorph in Baidun Collection Most Similar to Fig. 1121 on Page 241:

– P. Yule/A. Hauptmann/M. Hughes, “The Copper Hoards of the Indian Subcontinent: Preliminaries for an Interpretation”, Jahrbuch des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums Mainz 36, 1989 [1992], 193-275.

– “The Copper Hoards of the Indian Subcontinent: Preliminaries for an Interpretation” with Appendix I and II by Andreas Hauptmann and Michael J. Hughes (p. 239, fig. 1105; see also p. 241-242 figs. 1121-1123, 1128 for similar anthropomorphs).

– http://crossasia-repository.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/509/

– http://crossasia-repository.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/509/1/00jrgzm_all.pdf

cf. Scholarly Publication

– P. Yule, ‘Addenda to “The Copper Hoards of the Indian Subcontinent: Preliminaries for an Interpretation”‘

– http://crossasia-repository.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/510/

– http://crossasia-repository.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/510/1/yule_man_envir_2001.pdf

cf. Scholarly Publication

– P. Yule, “Beyond the Pale of Near Eastern Archaeology: Anthropomorphic Figures from al-Aqir near Bahla’, Sultanate of Oman” within: T. Stöllner et al. (Hrsg.), “Mensch und Bergbau Studies in Honour of Gerd Weisgerber on Occasion of his 65th Birthday”, (Bochum 2003) 537-542

– http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/propylaeumdok/109/1/Yule_2003.pdf

cf. Scholarly Publication

cf. Plates with Illustrations of Anthropomorphs:

– P. Yule, “Metalwork of the Bronze Age in India”

– http://crossasia-repository.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/1895/

– http://crossasia-repository.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/1895/1/Metalwork_BronzeAge_India.pdf

cf. Scholarly Publication

“The Copper Hoard Culture of the Gangā Valley”

– B. Lal (1972), “The Copper Hoard culture of the Gangā Valley”. Antiquity, 46 (184), 282-287. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00053886

– https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/antiquity/article/copper-hoard-culture-of-the-ganga-valley/EB6ABFD8D5BD193835C0145C3BD55925

cf. Scholarly Publication

– J. Manuel, “The antecedent’s diverse influences on and by Vaishnava Art, as perceptible from the times of Copper Anthropomorphic Figures” within:

Journal of Religious History South Asia, Vol. A-1 (Published Fall 2015)

– http://www.jorhsa.com/Edition_2015/Copper.pdf

cf. Scholarly Publication

“On Copper Age Anthropomorphic Figures from North India An Ethnological Interpretation”

Jürgen W. Frembgen

East and West

Vol. 46, No. 1/2 (June 1996), pp. 177-182

Published by: Istituto Italiano per l’Africa e l’Oriente (IsIAO)

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/29757261

Page Count: 6

cf. Scholarly Publication

“The Copper Hoards Problem: A Technological Angle”

D. P. AGRAWAL

Asian Perspectives

Vol. 12 (1969), pp. 113-119

Published by: University of Hawai’i Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/42929067

Page Count: 7

cf. Scholarly Publication

T.K.D GUPTA, “The anthropomorphic figures of the copper-hoards from India”

– https://www.researchgate.net/publication/306878726_The_anthropomorphic_figures_of_the_copper-hoards_from_India

Ancient Indus Museums

15 museums around the world where ancient Indus Civilization artifacts are live.

– https://www.harappa.com/museum

SOURCES

Links Included Above Embedded Inline + Links Below:

– http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.co.il/2016/07/all-four-types-of-anthropomorphs-of.html

– http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.co.il/2015/05/composite-copper-alloy-anthropomorphic.html

– http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.co.il/2014/01/stunning-metallic-ceiling-of-shivrajpur.html

– http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.co.il/2014/01/meluhha-hieroglyphs-snarling-iron-of.html

– http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.co.il/2014/01/stunning-metallic-ceiling-of-shivrajpur.html

– https://www.academia.edu/27354911/All_four_types_of_anthropomorphs_of_Copper_Hoard_Culture_are_dharma_saṁjñā_metalwork_signifiers_of_responsibilities_in_guild_or_professional_calling_cards

– https://sarasvati97.wordpress.com/2017/01/02/copper-anthropomorphs-are-dharma-saṃjna-संज्ञा-samskrtam-dhamma-sanna-सञ्ञा-pali/

– http://www.business-standard.com/article/specials/naman-ahuja-is-mastering-the-art-of-reaching-out-114092501180_1.html

REFERENCE #

SI_IN_1001

CIVILIZATION

Late Bronze, 1500 B.C.E. – 1300 B.C.E.

SIZE

Ht. 33 cm, Wd. 31 cm

CONDITION

Fine Condition.

PRICE

Price available upon request

PROVENANCE

Private English Collection, 1969