The origins of fresco painting are unknown, but it was used as early as the Minoan civilization (at Knossos on Crete) and by the ancient Romans (at Pompeii). The Italian Renaissance was the great period of fresco painting, as seen in the works of Cimabue, Giotto, Masaccio, Fra Angelico, Correggio and many other painters from the late 13th to the mid-16th century.

Fresco is a technique of mural painting executed upon freshly-laid lime plaster. Water is used as the vehicle (or medium) for the pigment, and with the setting of the plaster the painting becomes an integral part of the wall.

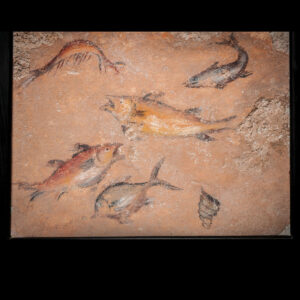

Roman Pompeian Wall Fresco – 3rd Style (Period)

This extremely fine fresco is an exquisite example of ancient Roman art, originates from Pompeii in ancient Rome, and is of the 3rd Pompeian Style that was popular 20-10 BCE. This 3rd Pompeian Style (and Period) emerged and developed as a reaction to the austerity of the previous period. It leaves room for more figurative and colorful decoration, with an overall more ornamental feeling, and often presents great finesse in execution. This style is typically noted as simplistically elegant.

One who beholds this fresco today wonders if the ancient Romans were making a first proto-attempt to illustrate the conceived notion of an aquarium before the advent of modern glass and other technologies that would make the invention of aquariums actually possible in the 19th century CE. It seems that the artist who painted this fresco was attempting to create a calm and relaxing environment for those who sat in the room whose walls were decorated with this fresco of swimming fish in an Aquarium-like motif – which was extremely innovative and insightful to have the foresight in his/her day 19 centuries before the advent and invention of glass aquariums!

Pompeii Destroyed by Volcanic Eruption of Vesuvius

On 24 August 79 CE, the city of Pompeii was destroyed by the violent eruption of the volcano Vesuvius. The eruption destroyed the city, killing its inhabitants and burying it under tons of ash. The circumstances of their destruction preserved their remains as a unique document of Greco-Roman life. Pompeii supported between 10,000 and 20,000 inhabitants at the time of its destruction. Fortunately for this Fresco, it also has survived and has remained intact in Fine Condition. Provenance is excellent: acquired in the 1980s, Ex. Private Swiss Collection.

The ruins at Pompeii were first discovered late in the 16th century CE by the architect Domenico Fontana. Herculaneum was discovered in 1709 CE, and systematic excavation began there in 1738 CE. Work did not begin at Pompeii until 1748 CE, and in 1763 CE an inscription (“Rei publicae Pompeianorum”) was found that identified the site as Pompeii. The work at these towns in the mid-18th century marked the start of the modern science of archaeology.

Mount Vesuvius erupted 24 August 79 CE. A vivid eyewitness report is preserved in two letters written by Pliny the Younger to the historian Tacitus, who had inquired about the death of Pliny the Elder, commander of the Roman fleet at Misenum. Site excavations and volcanological studies, notably in the late 20th century CE.

Just after midday on 24 August, fragments of ash, pumice, and other volcanic debris began pouring down on Pompeii, quickly covering the city to a depth of more than 9 feet (3 metres) and causing the roofs of many houses to fall in. Surges of pyroclastic material and heated gas, known as nuées ardentes, reached the city walls on the morning of 25 August and soon asphyxiated those residents who had not been killed by falling debris. Additional pyroclastic flows and rains of ash followed, adding at least another 9 feet of debris and preserving in a pall of ash the bodies of the inhabitants who perished while taking shelter in their houses or trying to escape toward the coast or by the roads leading to Stabiae or Nuceria.

Thus Pompeii remained buried under a layer of pumice stones and ash 19 to 23 feet (6 to 7 metres) deep. The city’s sudden burial served to protect it for the next 17 centuries from vandalism, looting, and the destructive effects of climate and weather.

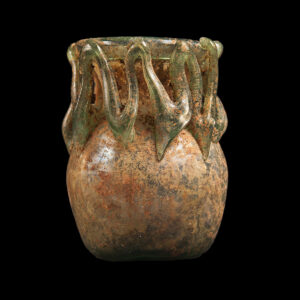

REFERENCE #

SW_MS_1103

CIVILIZATION

Roman, Pompeii 3rd Period, 100

SIZE

31 cm x H. 36.5 cm

CONDITION

Fine condition

PRICE

Price available upon request

PROVENANCE

Ex. Private Swiss collection, Acquired 1980s